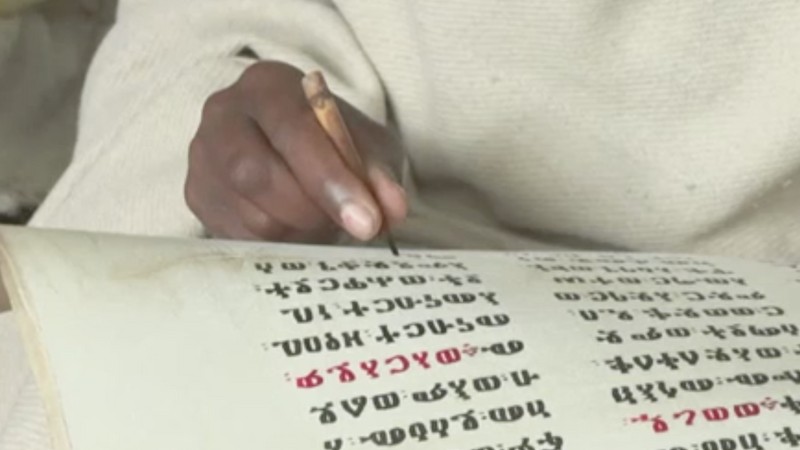

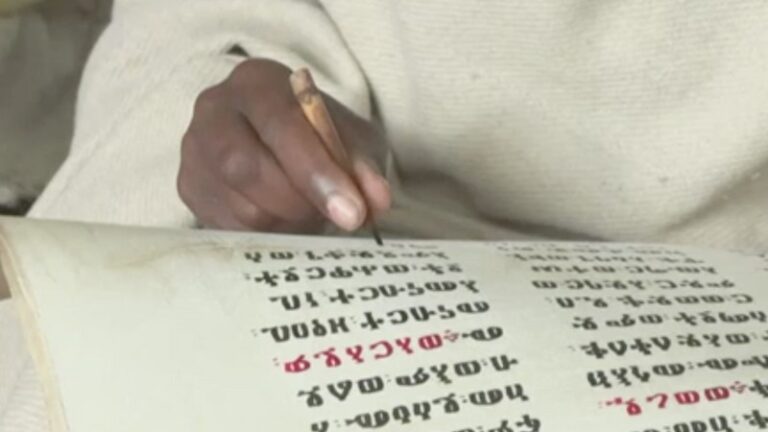

Ethiopian Orthodox priest Zelalem Mola meticulously copies ancient Ge’ez text from a religious book onto goatskin parchment using a bamboo ink pen. Zelalem, 42, states that this painstaking task helps preserve an ancient tradition and brings him closer to God.

At the Hamere Berhan Institute in Addis Ababa, priests and lay worshippers dedicate themselves to reproducing religious manuscripts and sacred artwork, some of which are centuries old. The institute, located in the Piasa district of the historic Ethiopian capital, prepares the parchments, pens, and inks on-site.

Yeshiemebet Sisay, 29, the head of communications at Hamere Berhan, explains that the project commenced four years ago due to the disappearance of ancient parchment manuscripts from Ethiopian culture. These valuable works are primarily found in monasteries, where prayers and religious chants take place using parchment rather than paper manuscripts. Consequently, Yeshiemebet and her team sought to learn the necessary skills from priests to undertake the replication work themselves.

In the institute’s courtyard, workers stretch goatskins tightly over metal frames to dry under the pale sun. The goatskins are soaked in water for several days before being tied to the metal frames and holes are made along the edge to facilitate stretching. Then, the inner layer of fat is removed to render the skin clean. The workers, including 20-year-old Tinsaye Chere Ayele, employ makeshift scrapers to complete their tasks, seemingly unperturbed by the strong odor emanating from the hides. Once clean and dry, the skins are stripped of goat hair and cut to the desired size for book pages or paintings.

Yeshiemebet reveals that most manuscripts are commissioned by individuals who later donate them to churches or monasteries. Some customers even order small collections of prayers or paintings for themselves, desiring reproductions of ancient Ethiopian works. The duration of the replication process varies; small books can take one to two months to complete, while larger volumes may require one to two years. Individual tasks can take even longer, as Yeshiemebet illustrates while leafing through books cloaked in red leather adorned with colorful illuminations and religious images.

In one of the institute’s rooms, Zelalem sits with parchment pages delicately resting on his knees as he patiently copies a book called “Zena Selassie” (“History of the Trinity”). The priest acknowledges that this task will consume a significant amount of time and effort. Starting with the preparation of the parchment and inks, the completion of this particular book may span up to six months. Zelalem explains that they fashion a stylus from bamboo, sharpening the tip with a razor blade. The scribes utilize different pens for each color used in the text, distinguishing between black and red ink. The inks themselves are derived from various local plants.

“Zena Selassie,” like many religious works, is written in Ge’ez. This dead language remains the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Its alphasyllabic system, where characters represent syllables, is still used to write Ethiopia’s national language, Amharic, as well as Tigrinya, spoken in Tigray and neighboring Eritrea.

Zelalem clarifies that copying from paper to parchment preserves the writings, as paper books are easily damaged, while parchments can endure if protected from water and fire. Replicating the manuscripts demands patience and focus, commencing with a morning prayer, continuing with devotion throughout the day, and concluding with prayer once the workday ends. Zelalem acknowledges the difficulty of an individual dedicating an entire day to writing and completing a book. Nevertheless, thanks to their devotion, they perceive a radiant light within themselves. The substantial labor invested in these tasks makes them worthy in the eyes of God.